by Al Reimer

When Thomas Wolfe set his strongly autobiographical novel Look Homeward, Angel (1929) in Asheville, North Carolina, his scathing portrayal of his hometown brought a public outcry so severe—he was even threatened with death—that he didn’t dare return to it for seven years. One would not expect responses to a Mennonite novel to be that violent, but Rudy Wiebe’s first novel Peace Shall Destroy Many (1962), which exposed some of the sacred cows of institutionalized Mennonitism, raised a storm that forced him to resign as editor of the Mennonite Brethren Herald in Winnipeg and gave him to understand he was no longer welcome in the community.

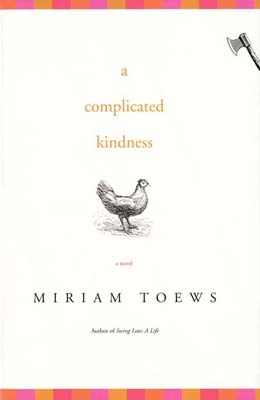

Nothing that drastic has happened to Miriam Toews, whose boldly satiric novel A Complicated Kindness is set in East Village, a fictional version of Steinbach, Manitoba. This highly acclaimed work has won Canada’s prestigious Governor General’s Literary Award and other prizes, is still on Canadian best-seller lists a year after publication and has been published to rave reviews in the U. S. and Britain. This “Mennonite” novel obviously enjoys a wide appeal among non-Mennonite readers and critics, but has raised the hackles of some Mennonite readers who know the Steinbach community and see the novel as a vicious attack against the town and, even more importantly, against the very principles of Mennonite faith and practice.

These hostile reactions to Toews’ novel have been hotly expressed in letters to the editor of The Carillon, Steinbach’s weekly paper. One writer calls the novel “a remarkably well-written rant” and states: “If we could leave it as a disaffected girl coming of age and bowing out, I could enjoy the novel. Unfortunately, Toews denigrates a religious faith and a thinly disguised prairie town.” Another letter charges that, “The author is clearly attempting to cast out personal demons by herding them into unsuspecting people and traditional institutions, past and present, in the Steinbach area.” The letter ends with the smug comment: “Many of us resolved our conflicts privately and perhaps positively, not in a continuing damning vendetta before an applauding audience.” A third letter accuses Toews of catering to “secular cultural elites’ tortured image of Steinbach in particular, and of Bible-believing Canadian Christians generally.”

In responding to this last letter, I dismissed this and other charges in it as “garbled nonsense and totally irrelevant to the novel in question.” It’s obvious that these letter writers have read A Complicated Kindness not as a novel—as pure fiction—but as irresponsibly distorted social history. The temptation to misread a novel from a historical perspective is almost irresistible when the reader is personally familiar with its setting. As a native Steinbacher, I too was distracted by Nomi’s negative view of the community and by her grossly distorted references to Mennonite history. It took a careful second reading for me to appreciate fully the brilliance of Toews’ literary achievement.

What makes the relationship between fiction and history somewhat ambivalent and confusing is that we are dealing with two equally valid but very different forms of reality: the imagined “real” world of fiction springs from our real world but is not confined to it, while history portrays that world as literally as possible. The German novelist Novalis claimed that, “Novels arise out of the shortcomings of history.” History is earth-bound by the “facts” we associate with the “real” world and unable to soar freely with the imagination, as fiction does. However, the facts of history also need to be “interpreted” and that, inevitably, requires a form of storytelling moving in the direction of imaginative fiction. Novels, however, can either ignore or adapt earth-bound facts to fit the requirements of imaginative storytelling. As often observed, the novel “shows” but never “tells,” as history is meant to do.

A novel makes an imagined world come alive as a fictionalized reality that deals with human experiences we all share. And because fiction sets up this alternative world of reality, controlled and directed by a creator who understands that fictive world, a novel can provide meanings and truths mythologized beyond the reach of history. But the reader can only enter that fictive world through ” a willing suspension of disbelief,” that is, by accepting that world as real in its own right and not as a falsification of the literal world. Fiction cuts away the superfluous fat of real life—its opacity, messy trivia, randomness and puzzling complexity—and gives us a leaner, more organized form of reality that can make sense where real life often doesn’t. That is not to say that fiction clarifies everything and/or neatly solves problems of human existence. Even the greatest of novels raise far more questions than they can answer. But raising questions for the reader is exactly what novels are designed to do. Nomi’s fictive function is to question everything in her small Mennonite world in a way social history never would (or could). The growing chaos of her life is a crucial learning experience for her, as well as a challenge for the reader to understand what is happening to her.

Imaginative storytelling is of course as old as civilization and without it there would be no history. Sophisticated readers of the Bible, while granting its ubiquitous spiritual cogency, would surely agree that it is written overwhelmingly in literary story form rather than as straight historical narrative. And stories involve characters, be they historical figures or fictional ones. Indeed, great fictional characters are so “real” they have a vitality and longevity that go far beyond the bounds of actual human lives. Shakespeare’s Hamlet has been a living entity for four centuries and is still going strong. Literary characters like Don Quixote, Emma Woodhouse, and Anna Karenina are as fully alive in their invented environment as we are in ours. Even a historical figure like Napoleon becomes a fully fictionalized character in Tolstoy’s War and Peace and must be experienced as such by the reader, although knowledge of the historic Napoleon will add body and resonance to the created character. But no matter how closely related, fiction and history must not be confused with each other.

Had Toews written a more “realistic” and “accurate” novel set in Steinbach, Mennonite readers might have said: “Yes, that’s the way it was. She’s got it right.” However, reading a novel that was little more than semi-fictionalized history would give them no new or unexpected insights and would raise no mental or moral challenges for them to confront. And certainly non-Mennonite readers would find it boring and not worth reading.

Instead, Toews gives us a colorfully dominant narrator who opens up this closed Mennonite community and offers an entirely new vision of it. Nomi, for all her eccentric ways and her moral and religious skepticism, is the heart and soul of the novel. She’s a fascinating, often bewildering, mix of intellectual brilliance and naivete, smart pop-art wit and emotional confusion, cockiness and self-deprecation, daring behavior and passive depression. But here’s the point: only a wild, unconventional and ever-questing rebel like Nomi could have so effectively revealed the dark underside of her Mennonite community. A more mature, fair-minded, and conforming narrator would never have exposed the repressive rules and sheer tyranny confronted by Nomi. In Nomi’s wickedly funny words, in East Village “You’re good or you’re bad. Actually, very good or very bad. Or very good at being very bad without being detected.”

This satiric view of the sinister side of Mennonitism is not to be construed as an all-out attack against Mennonite life and faith, as alleged by the letter writers above. It’s worth reminding ourselves that every community and its way of life, including the church, has a dark side that needs to be exposed and confronted and a novel can do that more effectively than social history. To deny that such a negative side exists in our Mennonite world is to endorse precisely the repressive good or evil orthodoxy which causes Nomi and her family so much suffering and spiritual terror. And what matters most to Nomi is her family, her one anchor in a sea of uncertainties. The dream of hope she never relinquishes is that her sister Tash and mother Trudie, along with her beloved father Ray, will return from their forced exile and miraculously restore her precious family to life again.

In the end, Nomi, for all her contempt, bitterness, grief, and moral ambiguity, begins to understand that even a community as cruelly despotic in its blind conformity as East Village, ultimately redeems itself with a kindness as complicated as its unkindness. And this theme of mysteriously conveyed sympathy and subtly implied empathy becomes a blessing of grace for Nomi that expands into a universal theme of loss, suffering, and redemption.

That this universal theme emerges in the end, however paradoxically rendered as “a beautiful lie,” attests to Miriam Toews’ skill as a serious novelist. Her caustic wit and unrelenting irony, entertaining as they are, lead inexorably to a conclusion that goes well beyond witty entertainment, mere satire, and cultural denigration. It is this verbal vision of reality that illuminates and engages the reader who reads a novel for its truths and insights and not for its historical discrepancies and distortions of the “real” world we live in.

Al Reimer, a Berliner Kehler, is Professor Emeritus of English at the University of Winnipeg. He is the author of ‘Mennonite Literary Voices: Past and Present’ (Bethel College, 1993).